Starting a Game Session: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

Treat any partial hex as equal to a full hex. This allows a realistic representation of either a hex-walled room or an irregular cavern. | Treat any partial hex as equal to a full hex. This allows a realistic representation of either a hex-walled room or an irregular cavern. | ||

==Player-Made Maps== | |||

Whenever the PCs enter an area for which they have no map – be it a dungeon, a laboratory complex, or a network of jungle trails – the players will want to map it themselves. (That is, they will if they are smart!) | Whenever the PCs enter an area for which they have no map – be it a dungeon, a laboratory complex, or a network of jungle trails – the players will want to map it themselves. (That is, they will if they are smart!) | ||

Latest revision as of 16:14, 25 August 2021

Starting a Game Session

There are a few things the GM should do before play actually starts, to make things easier for himself and the players:

Introduce the characters. If you are in the middle of a continuing campaign, you can skip this step! But if you are just starting out, each player should have the opportunity to describe "himself" or "herself." If there is an artist in the group, he may help by drawing the characters as they are described.

Check for skills, etc. improved since the last play session. In a continuing campaign, the PCs earn character points that they can spend to improve their abilities. Sometimes the PCs can study, work at jobs, etc. between play sessions. Therefore, some characters may have better skills or abilities than they did last game session. This is the time for the players to work out such matters with the GM. (If everyone in the group has net access, it might be better to work on this via e-mail between games, to avoid slowing things down.)

Fill out the GM Control Sheet. While the players are getting to know each other (or each other's characters), the GM should check over the character sheets, make sure everything balances, and copy necessary information onto a GM Control Sheet. This reference lists attributes, secondary characteristics, special advantages and skills, etc. for each PC. When the GM rolls in secret to determine who sees something, who understands something that everyone sees, who resists a spell, or who that bad-tempered dwarf takes a dislike to, this sheet is valuable.

Brief the players. Tell them what's going on, give them some idea what the adventure will be about, and (in a continuing campaign) refresh their memory about the last game session. There are many ways to do this. You can always just tell them. But it's much more fun to start play and then "set the scene." Let the characters immediately find a map or old book...meet someone who tells them an interesting rumor...befriend someone in need of help...witness a wrong that needs righting...or whatever.

Let the game begin!

Advance Preparation

There are several things for the GM to do well in advance, before the players arrive on the scene:

Prepare the adventure. If you are playing a prepared adventure, all you need to do is read through it, and possibly make up some character sheets. But if you are designing your own adventure, you may spend weeks of work – a labor of love – before it is ready for the players. In any event, be sure you're fully familiar with the adventure before the players show up!

Brief the players about the adventure. If your players are already familiar with the system, you should tell them in advance (before they arrive to start the game) what sort of characters are "legal" and how much money, equipment, etc. they are allowed – and perhaps give a hint about useful skills. If everyone has his character made up in advance, you'll be able to get right to the action when the players arrive. Set up the play area. You need pencils, paper, and dice; maps and miniatures if you are using them (and a table to play them on); and a supply of snacks (for yourself, if not for the whole group)!

Who's Got the Sheets?

Much of the advice in this chapter assumes that you, as GM, have access to the character sheets during the planning process, or at least are maintaining a detailed GM Control Sheet. Some GMs ask the players to leave their character sheets with them, both because it helps them plan and because then the players can't lose them. However, there are situations (for instance, a campaign in which GM duties rotate through the group) where that's impractical – and some players really don't like to give up that much control. You should at least have a control sheet with each PC's primary abilities, updated as major changes happen. It's not as good as having the actual character sheets, but it’s much better than trying to plan and run the game blind. Of course, a photocopy or digital copy is even better!

To Screen or Not to Screen?

Many GMs prefer to use folders, books, or other opaque items to screen their notes and die rolls from the players. Others find that it distances them from the game, and like being right out with everyone else. This is largely a matter of taste; we point out only that there are situations in which a GM should roll secretly, and you should have some easy way to do that.

Maps

Mapping Overland Journeys

If the PCs are traveling through unexplored territory, the players may wish to keep a large-scale map. The GM may make it automatic if they are following rivers, canyons, and the like. If they are trekking through featureless wastes, or trying to map a specific tiny inlet of a great river, making a map good enough for others to follow requires a Cartography roll. This defaults to IQ-5, Geography-2, Mathematics (Surveying)-2, or Navigation-4. Absolute Direction is good for +3 to the roll.

This can be an adventure in itself: the party is sent to explore and map the trackless waste, virgin planet, mysterious dungeon, steaming jungle, dead city, or whatever.

The GM may wish to prepare maps in advance, to help him plan and to keep track of events. He may also give maps to the players as clues. And the players themselves might want to map their progress – whether it be through jungles, dungeons, or downtown New York City – to make sure they can find their way back...

Maps in GURPS use hexagons, or "hexes," to regulate movement and combat. Each hex is adjacent to six other hexes. See Hexes.

Travel Maps

Draw these maps to any convenient scale. Examples include maps of continents, highways, and cities. These are purely for information; they are not "playing boards." In a modern adventure, the players have access to travel maps. In a far-past or far-future campaign, the travel map might be the GM's secret. (Finding a map can be a great adventure objective.)

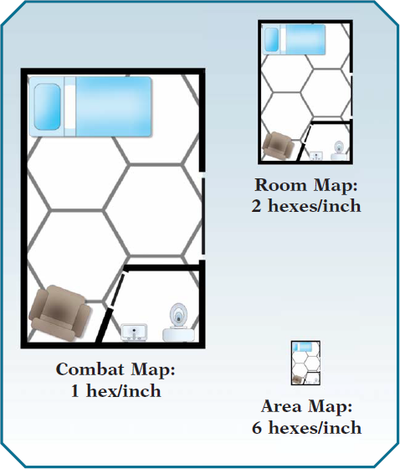

Area Maps

The standard scale for these maps is 1” = 18’ (6 hexes). Each hex is still one yard across – it is just drawn to a smaller scale. Use this scale to map an entire building, dungeon, arena, etc., and use a different sheet for each floor or level, indicating shafts and stairways. Mark each room (or other point of interest) with a letter or number for use with a map key.

For each room, the map key should give:

- Its size (although this might be clear from the area map).

- A general description.

- A description of the people or creatures in the room, if any. This may be as simple as "Two ordinary wolves," or as complex as "This room is empty except between midnight and 9 a.m., when two guards are there. There is a 50% chance that each one is asleep. They are ordinary guards from the Character List, but one of them also has a gold ring worth $200. They will surrender if outnumbered more than 2 to 1, but will not cooperate, even if threatened with death."

- If necessary, any special notes about the room, and descriptions of anything that might be found if the room were examined carefully.

- If necessary, a room map (see below) to show the precise location of furniture, characters, etc.

The GM should keep this sort of map secret from the players – although they can try to make their own map. He may wish to place a marker on the area map to show where the party is at any given moment.

Room Maps

Draw these maps to any convenient scale. A useful scale is 1" = 6' (2 hexes) – half the size of a combat map. Use these maps when you need to sketch a room in some detail but do not want to draw up a combat map.

Combat Maps

Combat does not require combat maps – although they can be handy to help the players visualize the action. Tactical Combat does require combat maps.

Combat maps are drawn to a scale of 1" = 3'; each hex is three feet, or 1 yard, across. When the characters enter an area where combat might occur, lay out a map and have them place their figures on it to show exactly where they are. If combat occurs, play out the fight on the combat map.

Treat any partial hex as equal to a full hex. This allows a realistic representation of either a hex-walled room or an irregular cavern.

Player-Made Maps

Whenever the PCs enter an area for which they have no map – be it a dungeon, a laboratory complex, or a network of jungle trails – the players will want to map it themselves. (That is, they will if they are smart!)

However, mapping is not trivial. Unless the party carries a tape measure and spends a lot of time using it, you should not tell them, "You go 12 yards down the stairs and turn north. The tunnel is seven feet wide and nine feet high. It goes north for 120 yards and then turns northeast. In another 20 yards, it opens out into a room 10 yards by 6 yards." That sort of information would require several minutes per measurement and a skill roll against Mathematics (Surveying) – not just a stroll through the tunnel!

Instead, give them information like this:

- "You walk down the stairs – they go down a little farther than an ordinary flight of stairs. At the bottom, there's a tunnel going right. It's wide enough for two to walk side by side, and so high you can barely touch the ceiling with your swords. It goes on for a ways in a fairly straight line..."

- "How far?" asks a player.

- "Is somebody pacing it off? Okay. Around 128 paces. It then turns to the right a bit..."

- "How much?"

- "Did you bring surveying tools? Anybody got Absolute Direction? No? All right. Standing at the intersection, with the old tunnel behind you at six o'clock, the new tunnel looks like it turns away at between one o'clock and two o'clock. Got that? Now, it goes along for another 19 or 20 paces, and then opens out into a bigroom. The door is in the middle of the long wall. The room is roughly rectangular. From where you stand, it might be 10 yards long, 6 or 7 yards wide."

Very different, yes? But also much more realistic. The players receive only the information the PCs actually get with their senses. In the example above, the GM fudged all the distances a little bit, assuming that whoever was pacing would have a standard pace a bit less than a yard.

If you do this, the players might come up with ingenious ways to measure time and distance. Let them!

Note that if mapping is difficult in ordinary circumstances, it becomes next to impossible if the party is in a hurry! Suppose the group is being chased through the area described above. The GM would say:

- "Okay. You're running? Stop mapping. Here's where you go. Down the stairs! Turn right! Run for several seconds! The tunnel bends to the right! Run a little farther! You're in a room!"

And so on. When the party stops running, they can sit down and try to remember where they went. (Eidetic Memory is a big help here!)